TP calorimetry

Goal : use of calorimeter to measure thermal (heat) capacities and latent heat.

Some theoretical aspects

Generalities

Calorimetry is based on the laws of thermodynamics and it enables to measure heat capacities, latent heat and the heat of the reaction. What you need to know about this practical work :

- In calorimetry, the transformations occur at constant pressure (they are isobar). In that case, the transfer of heat that is received by a substance, liquid or solid, upon the variation of temperature from $T_i$ to $T_f$ can be expressed by the following relation: \[ Q_P=\int_{T_{\text{i}}}^{T_{\text{f}}} n\,c_{\text{pm}}(T)\,\mathrm{d}T \] where $n$ is the number of moles (mol), $c_{\text{pm}}$ the molar heat capacity (J.K-1.mol-1) and $T$ the temperature (K).

- In the interval of explored temperatures in this practical work, we can consider that thermal capacities are constant. It follows : \begin{equation} \boxed{\displaystyle Q_P=n\,c_{\text{pm}}(T_{\text{f}}-T_{\text{i}}) }\quad \heartsuit \label{eq:chaleur_recue} \end{equation}

- There are other definitions for thermal capacities as:

- the specific heat capacity of the object $c_p$ in units of J.K-1.kg-1

- the heat capacity (or total heat capacity), $C$, in units J.K-1. $C = m\,c_p = n\,c_{\text{pm}}$.

- Liquids or solids may undergo a phase change (solidification or fusion). This phase transition is accompanied by a heat transfer at one temperature that remains constant during the phase transition. As an example, to transform a solid into a liquid, it has to be heated up to the temperature of fusion and then a certain amount of heat has to be brought, that is called the latent heat of fusion, defined as : \begin{equation} \boxed{\displaystyle Q_P=mL_{\text{f}} } \quad \heartsuit \label{eq:chaleur_latente} \end{equation} The latent heat of fusion, $L_f$, en J.kg-1 depends on characteristics of the pure substance.

In all this practical Work, we can evaluate the uncertainties : the calculs can be make with Regressi, it will be easier than with the hand.

Heat capacity of the Calorimeter

To prepare

Do a research for to understand what is the signification to the equivalent mass in water of calorimeter.

The instrument that is used to measure heat exchanges and heat capacities is a calorimeter. An ideal calorimeter is adiabatic: there is no thermal exchange (exchange of heat) between the calorimeter and its environment. Therefore, in an ideal calorimeter that contains two systems, one of these systems receives the heat $Q_1$ while the other receives the heat $Q_2$, the following equation holds: \begin{equation} \boxed{\displaystyle Q_1+Q_2=0 } \quad \heartsuit \label{eq:relation_calorimetrique} \end{equation} In this practical training we assume the hypothesis that the calorimeter is perfectly adiabatic.

In calorimetry it is often desirable to know the heat capacity of the calorimeter itself rather than the heat capacity of the entire calorimeter system (calorimeter and water). We therefore introduce an expression “the water contents of the calorimeter” that we denote $\mu$. We consider, what concerns thermal exchanges, the calorimeter and its accessories are equivalent to a certain mass of water, \(\mu\). Thus, when the temperature of the calorimeter changes from $T_1$ to $T_2$, we must take into account that it has received a heat \begin{equation} \boxed{Q_{\text{cal}}= \mu \times c_e (T_2-T_1)} \quad \heartsuit \end{equation} with $c_e$ specific heat capacity of liquid water, that is 4180 J.K-1.kg-1 and $\mu$ the equivalent mass of water for calorimeter (kg).

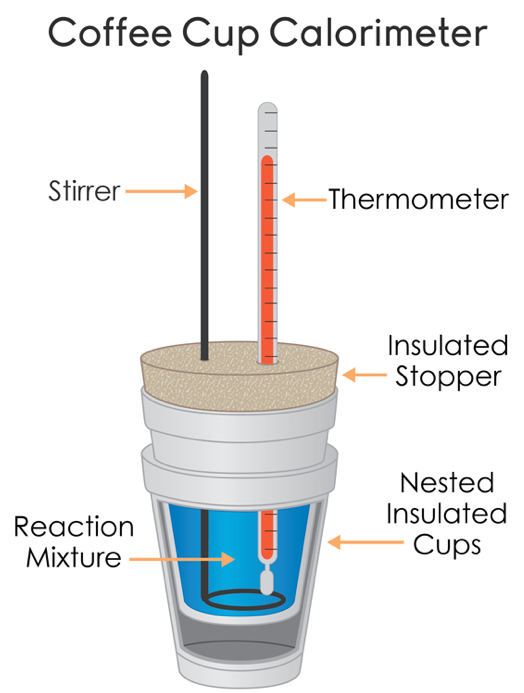

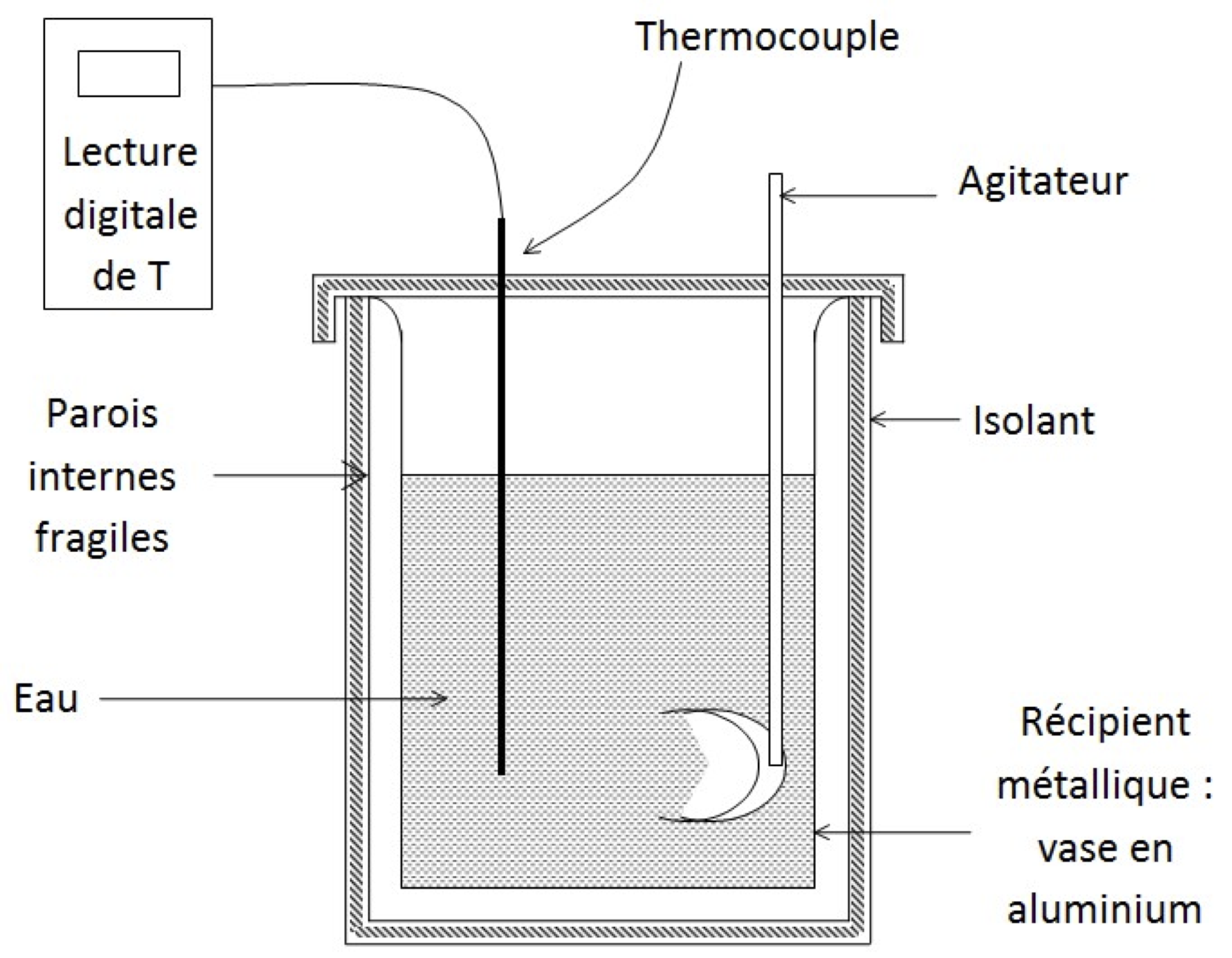

Experimental apparatus

The calorimeter is as a thermos bottle, this in order to reduce heat losses : the instrument then becomes almost an adiabatic calorimeter. It consists of an insulating wall, a container into which the liquids will be poured, a lid that will be carefully closed and an agitator to accelerate the thermal equilibrium.

The quality of the results will depend on how you will do everything possible to reduce heat loss with the outside.

To heat liquids, use a kettle or an electric plate. The temperature is read using a thermocouple thermometer with digital reading on housing : use 0,1$^\circ$C accuracy.

Finally, pay attention to devices and instruments : they are expensive and fragile.

Manipulations

Determination of the heat capacity of the calorimeter

- In the calorimeter, introduce $m'$ grams (not more than about 100 g) of water at room temperature.

- \(\spadesuit\) Note the equilibrium temperature \(T_i\).

- \(\spadesuit\) Prepare a mass $m$ (not less than 200 g) of warm water at a temperature $T_0$ between 25$^\circ \mathrm{C}$ and 40$^\circ \mathrm{C}$. Note $T_0$ then put into the calorimeter.

Homogenize with stirring - \(\spadesuit\) Note the new equilibrium temperature $T_f$ (it corresponds to the minimum temperature reached in the calorimeter) and determine the total mass of water to know precisely the mass of warm water poured.

To prepare

- Express the amount of heat \(Q_1\) received by the hot water ;

- Express the amount of heat \(Q_2\) received by the calorimeter and the cold water ;

- The calorimeter is supposed to be ideal. Deduce the expression of the equivalent mass of the calorimeter \(\mu\)

- \(\spadesuit\) Calculate $\mu$. The determination of $\mu$ is important for the future measurements, that is why you are asked to make two measures of $\mu$ (steps 1, 2, 3 and 4).

With the second group, you have four measures. Use Student protocol (Regressi) for calculate an incertainty of type A. Have the value of $\mu$ checked with the teacher.

Determination of the heat capacity of the metal

- Choose a piece of metal and determine its mass $M$. Bring it to the temperature T0 = 100$^\circ \mathrm{C}$ by putting it in the boiling water of the pan (wait long enough). This piece of metal should not touch the bottom of the pan (which is not 100$^\circ \mathrm{C}$).

- \(\spadesuit\) Put a mass $m$ of water in the calorimeter. Note the temperature $T_i$ of the water.

- Immerse the piece of metal in the water of the calorimeter.

Homogenize with stirring - \(\spadesuit\) Measure $T_f$ at thermal equilibrium.

To prepare

- Express the amount of heat $Q_1$ received by the metal ;

- Express the amount of heat $Q_2$ received by the calorimeter and the water at room temperature ;

- The calorimeter being supposed to be ideal, deduce the expression of the specific thermal capacity of the metal $c'$ as a function of \(T_f\), \(T_0\), \(T_i\), \(m\), \(\mu\) et \(M\).

- \(\spadesuit\) Calculate \(c'\). Estimate its incertainty. Comparate with the theorical value.

Determination of the latent heat of ice melting

- \(\spadesuit\) Put a mass $m$ of hot water in the calorimeter. Note $T_i$. Choose mass of ice all the greater than $T_i$ is large.

- Take a mass $M$ of ice at the temperature $T_0 = 0^\circ \mathrm{C}$. Important : The ice must not begin to melt before use. Put this ice in the calorimeter. Homogenize with stirring.

- \(\spadesuit\) Measure the temperature $T_f$ at thermal equilibrium : the ice must be completely melted and the temperature must not vary much anymore.

- \(\spadesuit\) Determine the mass of ice by weighing the total mass of liquid in the calorimeter.

To prepare

- Express the amount of heat $Q_1$ needed to melt the ice ;

- Express the amount of heat $Q_2$ required to heat the melted ice from $0^\circ \mathrm{C}$ to \(T_f\) ;

- Express the quantity of heat $Q_3$ received by the water and the calorimeter initially at the temperature $T_i$

- Deduce the expression of the mass latent heat of ice.

- \(\spadesuit\) Determine the latent heat of melting ice $L_f$ from your measurements. Estimate its incertainty. Comparate with the theorical value.

Determination of the specific heat capacity of ethanol

- \(\spadesuit\) Take about 100 cm3 of water and cool with about 20 g of ice to $T_i= 5^\circ \mathrm{C}$. Measure the mass, $m$, of water accurately. Put this water in the calorimeter. Record the temperature $T_i$ of the water.

- \(\spadesuit\) Measure and record the temperature of ethanol in its bottle, $T_0$. Pour a mass $m_0 = 50 \mathrm{g}$ (to measure exactly) of ethanol into the calorimeter.

Homogenize with stirring. - \(\spadesuit\) Measure $T_f$ at thermal equilibrium.

- \(\spadesuit\) Following the same procedure as in experiment 3.2., determine the specific heat of ethanol $c_0$.

- \(\spadesuit\) The tables give \(c_0 \simeq 2500\,\mathrm{J.kg^{-1}.K^{-1}}\). Is your measurement consistent with the tables according to you ? If not, propose an explanation.

- \(\spadesuit\) Propose another protocol to measure the thermal capacity of ethanol and realize it (if time permits).

Results sheet

Go to your space LabNbook for sending your results.

Matériel

- a calorimeter ;

- a scale ;

- pieces of metal ;

- a wood peach ;

- a kettle.